Is Artificial Intelligence smart enough to make our evaluation work easier, and how far we can go with using it?

Evaluators are interpreters. Conversations with real people, at the grassroots, happen in simple, everyday language. Evaluators translate them into the jargon used in development talks and reports (where people are “empowered”, “aware”, “mobilized”, “create platforms” or “demand their rights”), to make them more fit for analysis and sharing.

When I started using videos in my work – capturing soundbites from these conversations – I discovered how development and humanitarian professionals, with little exposure to the grassroots (and too often used to the lingo), may be deceived by the simplicity of everyday language, and fail to see the point.

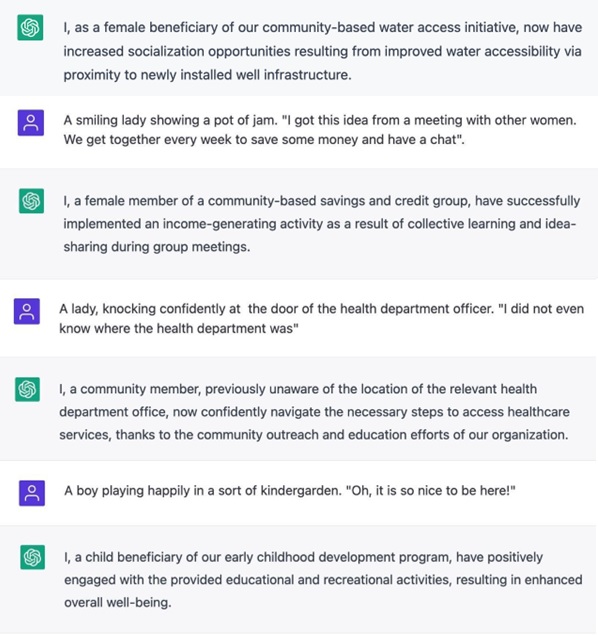

For example, one video featured a woman benefitting from a water project. Water was now close to her home, not miles away.

When asked what change she experienced with these new wells, tongue-in-cheek she proudly showed the coffee she was enjoying with other women: “Now I have the time to drink coffee with my friends!” She did not talk about chores. She enjoyed her free time and social life. A wonderful, unexpected outcome. But… this video fell flat.

I was asked: "What does coffee have to do with a water project?" And this was not a one-time comment. “Soft” changes are often hard to pick up and value. Change is found in translation, when it would be lost in everyday words. And change can be better appreciated when translated into jargon.

So it’s true, evaluators need to be interpreters and read between the lines. They shall translate achievements and challenges into the lingo used by the development and humanitarian community so that significant changes can be valued and appreciated. And also for convenience of analysis.

I was curious: would AI get it? Could it be a good interpreter?

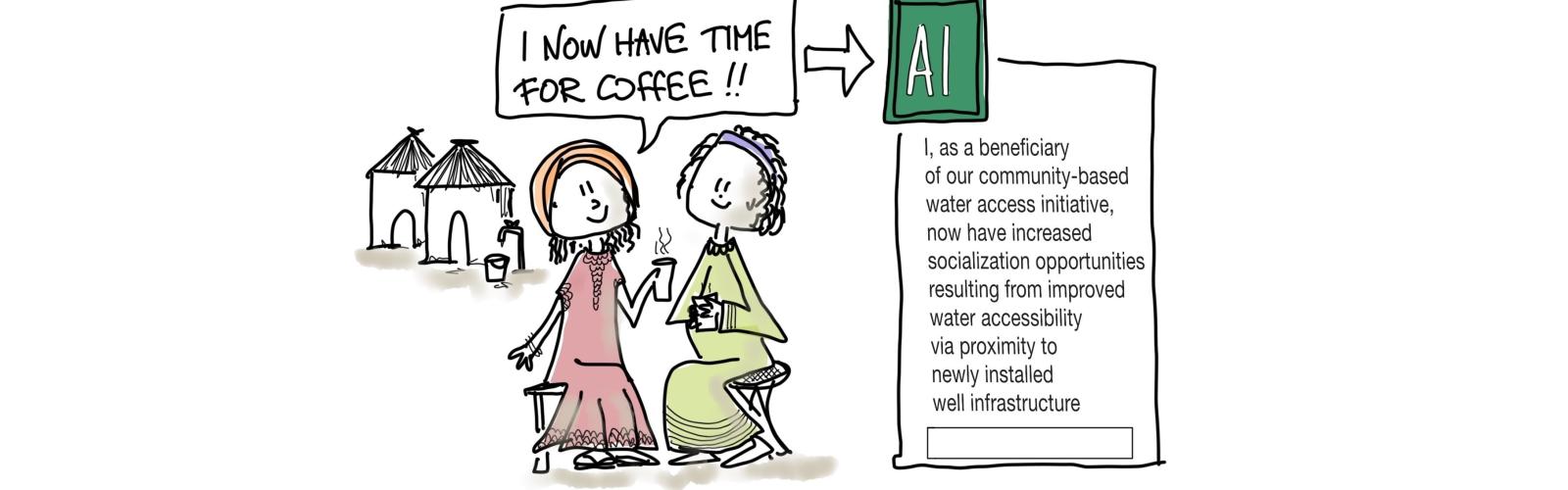

I prompted ChatGPT to translate simple sentences into humanitarian / development lingo:

" Let's play a game. Imagine a seasoned development practitioner/bureaucrat who only understands lingo, jargon, project proposals, and reporting language. This person does not understand colloquial sentences. I will now present you with sentences said by real-world people. You need to translate them for the practitioner in development jargon. Is this clear?

“Sure” ChatGPT confidently replied!

And indeed it was good.

ChatGPT could go even further. I prompted it to check if and how these sentences match pre-established criteria. It was excellent at the job (and could also provide formats suitable for Excel export). But I will leave this topic for another article!

So, what is left for us?

First of all, get the sentences.

The sentences used as examples are the result of human engagement: being there, establishing trust, spotting a significant turn in the conversation, and following up on it with curiosity and active listening.

ChatGPT is very good at translating sentences but not (yet?) at leading conversations or picking up on what is most significant. Having said that, AI tools can already provide a good list of standard questions. Linked chatbots can facilitate and analyse free-flowing conversations on predetermined topics.

But they surely still lack the presence, the instinct, the connection that can transform a Q&A session into a conversation. And they lack the emotions that ultimately shape conversations and trust.

Discovering emerging criteria.

Qualitative analysis can start from pre-set criteria: we check if / how evidence matches them. Standard evaluation criteria and set evaluation questions can be explored with this deductive type of analysis.

This approach works well when we already know what we are looking for. Qualitative analysis might also be used to reveal patterns, themes, ideas not initially apparent. Inductive qualitative analysis is a completely different approach: it is more exploratory and open to the possibility of unexpected findings. ChatGPT can also look for emerging criteria, but pinpointing emerging criteria and evidence is still more of an art.

ChatGPT goes for the patterns, for what is statistically recurrent. And in doing so, it might even help us to reveal our own bias. Humans also use their curiosity, intuition, sensemaking and non-textual clues to discover what stands out, the deviances, the gaps. Their subjectivity and intuition work better in complex setups.

As ChatGPT put it, “if the data is structured and quantitative in nature, my ability to identify emergent criteria may be more limited… some types of criteria may be more challenging for me to identify. For example, I may find it hard to identify complex social or cultural phenomena that require a deep understanding of context or domain expertise.”

Pinpointing innovative ideas.

Linked to the above, ChatGPT might quickly understand that a group is a “self-help” group… but it would struggle to discover what makes this group unique, or its untold challenges and potential.

Experienced evaluators might instead read all this between the lines (and enquire further). By being so focused on explicit trends and patterns, ChatGPT risks flattening narratives.

Whilst it could brainstorm all sort of generic ideas out of the blue, it has a much harder time at revealing real seeds of innovation: this requires to be tuned in and connected with reality.

We are still much better at finding what is unique, at feeling novel directions (and yes, ChatGPT also agrees on this: “While ChatGPT can quickly identify trends and patterns, it may struggle to identify unique or innovative ideas that may not fit within pre-existing categories or frames. Human intuition and creativity are still essential for recognizing and appreciating novel ideas.”)

Break standardized interpretations.

ChatGPT might look insightful, but… it does not think! It does not truly “understand”. It just recombines words to produce credible sequences: the most probable combinations based on the huge amount of information it digested. Even its most profound essay is a product of statistics, not reality.

Its outputs are shaped by ideologies and worldviews prevalent in the body of knowledge it has absorbed, and by the formats used in its training (which are, incidentally, not disclosed). It is very important to keep this in mind.

When we ask ChatGPT to interpret evidence, we introduce a bias: we are reverting to mainstream thinking structures.

When we feel it does a good job in processing and summarizing evidence – as it did above – it is because this is how such job tends to be done in the organizations and setups we work in.

It is because it mocks our language, not because it is the best possible understanding.

What are the possible risks?

To miss out on alternative epistemologies, heuristics, on other perspectives and angles.

They might not be so polished, yet more meaningful and relevant. Eventually, ChatGPT future versions might be nourished with alternative narratives and worldviews. But this requires availability of products and materials exploring diverse realities and possibilities, articulating different interpretations.

It might become a vicious circle! The evaluation community can have a major role in revealing and propagating alternative worldviews and understandings, given its unique exposure to change. Even more so, evaluators working in development, humanitarian and peacebuilding projects are exposed to diverse cultures, setups and very complex situations.

Doing things exactly “by the book” is both the blessing and the curse of ChatGPT. We could just go the easy way, doing “more of the same” at a faster processing speed. But if more and more knowledge accumulate, based on the same frames, resistance to new interpretations might be further increased. Or we could make good use of the time we save: once ChatGPT helps us to identify “the usual findings or interpretations”, we could then put our intuition, imagination, awareness of reality to good use: are they valid? Should we interpret evidence differently, with different lenses? What voices and perspectives should we value most? If we stick to conventional evaluation, ChatGPT new incarnations will soon be as good as us. And probably largely replace us. If we liberate our thinking and creativity, embracing alternative approaches, we might collaborate with it to reach deeper insights.

Vicente Plata

ConsultantDear Silva, you are absolutely right. Evaluators are mainly interpreters of what has happened, and consequently not only a "tick the box" in a "multiple choice" questionnaire. Of course we have to fill some forms and tables, organize information in a pre-agreed way, but the most important work is when we are able to find a "non previewed" result or impact. Most of our work is "standard work" and it has to be "up to standard", but there is a piece of "original work" that is what adds brightness to the evaluation work. And that cannot be done by AI, as AI always is an "average" of previous experiences.

Best

Vicente Plata

Alena Lappo Voronetskaya

Evaluation Officer (IAEA); Board Member (European Evaluation Society)Hi Silvia!

Thank you for the blog. Your review of the ChatGPT that highlights the strength and weaknesses of this software is greatly insightful. We shared the blog through the European Evaluation Society Newsletter today so that more members of evaluation community can participate in the discussion on technology and evaluation you raised through this blog.

Referring to the question you posed on whether AI in general is smart enough and can make our evaluation work easier, my answer is yes if we as evaluation practitioners understand its application and limitations.

Firstly, good evaluation always starts with the right evaluation questions and the methodology designed to answer these questions that take into account contextual factors, limitations, sensitivities, etc. I understand, that your example about coffee suggests that the value should have been placed on “time saving” and not on less “chores”. Methodologies such as Social Return on Investment (SROI) could go further in this example and place value, even financial, on the social activity of drinking coffee with friends beyond “time saving” if this is relevant to answer evaluation questions. This to say, “extra free time” and enriched “social life” should be of interest for the evaluation before the decision on whether to use AI technology for data collection/analysis and the search of the most appropriate software package.

Secondly, it is important to understand the limitations of applying AI and innovative technologies in our evaluation practice. To provide more insights into the implications of new and emerging technologies in evaluation, we discuss these subjects in the EvalEdge Podcast I co-host with my EES colleagues. The first episodes of the podcast focus on the limitations of big data and ways to overcome them.

Thirdly, the iterative process of interaction of evaluator and technology is important. As a good practice, data collected through innovative data collection tools triangulated with data collected through other sources. Machine learning algorithms applied, for example, to text analytics as discussed in one of the EES webinars on “Emerging Data Landscapes in M&E” need to be “trained” by human to code documents and to recognise the desired patterns.

Best regards,

Alena

RFE Réseau francophone de l'évaluation

Réseau francophone de l'évaluationBonjour Silva,

Merci beaucoup pour le lancement de cette discussion sur l'évaluation et Chat GPT. Je suis pressé de lire les réactions car ce sujet sera probablement abordé lors de la 5e édition du Forum international francophone de l'évaluation que le RFE (Réseau francophone de l'évaluation) organise avec la SOLEP (Société luxembourgeoise de l'évaluation et de la prospective), les 4, 5 et 6 juillet prochain, à Luxembourg.

Si le français n'est pas un problème pour toi, je t'invite à soumettre une proposition d'intervention d'ici le 30 mars. Cette invitation à nous adresser des propositions d'interventions vaut également pour l'ensemble des membres de la communauté EvalForward. Les dépôts se font en ligne : www.fife2023.rfevaluation.org.

Le thème de l'événement est "Évaluation et révolution numérique".

Jean-Marie Loncle

Secrétaire permanent du RFE