As evaluators, we are faced with the growing complexity of the times in which we live and the challenge of making our mark on development efforts to create a better world. The COVID-19 experience showed us the way forward.

A step back in time

If we go back to the turn of the century, we can see how much the development assistance paradigm shifted from the 1990s to the 2000s. Rather than seeing development as something that should be taught and provided, it was recast as a largely home-grown process that could be supported and facilitated by external partners. As national ownership of the development process became more widely recognized, so the conditions for development assistance changed to prioritise the commitment of national governments and partners to agreed development goals. Thus, many countries started to build development strategies that aimed to achieve high-level strategic goals. At the global level, governments signed up to the Millennium Development Goals.

In a similar vein, evaluations needed a shift in approach. With the dawn of the new millennium, evaluators were not only required to examine the operational effectiveness of interventions and policies, but also their linkages and contributions to higher-level development goals and policy objectives. This created the challenge of analysing multisectoral complexities, which we still struggle to dissect today.

How to approach complexity

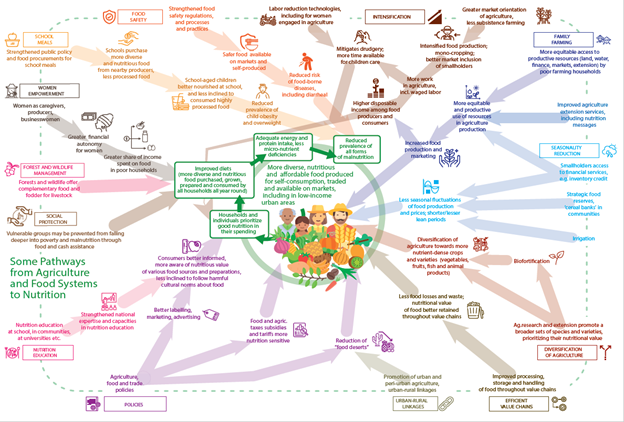

One way to approach complexity and see the bigger picture of an intervention or programme is to draw what we call a systems map. Here is an example of what we produced when we evaluated the nutrition strategy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as part of our evaluation of the Organization’s contribution to Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2).

The map shows intersectoral synergies and trade-offs embedded in the system that create dynamic processes with a degree of unpredictability. Of course, this is too complex to analyse in its entirety, nor can it be used to measure the effects of interventions. No one is expected to understand the entire system.

How, then, do we approach such complexity and unpredictability in programming and in monitoring and in evaluation? The answer is to take an adaptive approach, which focuses on producing the desired results while adjusting the actions required to achieve them. It is crucial to anchor the results you want, then monitor and analyse the way in which these results are achieved. Most importantly, we must take a learning approach, so that when things go wrong or do not work out as expected, we examine the reasons and take corrective measures. It is also important to do this in a transparent way, as the project has deviated from its initial intention.

What can we learn from the response to COVID-19?

The global COVID-19 response is a good example of dealing with multisectoral complexity. There are clear trade-offs between containing the virus and keeping the global economy going. Both the pandemic and measures to counter it affect people in different ways and to varying degrees, creating dynamic processes that are unpredictable.

No one can analyse all of the effects of a policy in such a situation, be it lockdown or an easing of restrictions. Experts on infectious disease have their opinions. Economists and sociologists have theirs. And at the end of the day, politicians make a call, based on the advice of various sectoral experts.

In doing so, they should also be able to draw on results-based monitoring data – rates of infection, death and hospital capacity, for instance, and a plethora of socioeconomic indicators. It is also important that decision-makers have analysis of why certain data have gone up or down, so as to take an informed judgement. This adaptive approach has been a natural response during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the face of huge multisectoral complexity and unpredictability. It is, possible, therefore, to practice an adaptive approach with a focus on achieving results in the face of such a crisis.

This is actually what evaluations are supposed to do: look at the data and evidence, focus on results indicators, analyse the causal relationships behind them and provide evidence-based policy advice.

Real-time evaluations are an appropriate approach

The head of our organization asked the Office of Evaluation to undertake a real-time evaluation of our programme to combat the desert locust plague, amid an emerging crisis in East Africa and western Asia. The locust swarms were predicted to have a devastating impact on agriculture in both regions. The Director-General wanted our evaluators to use their expertise to provide analysis and policy advice, based on results data and evidence, while the programme was ongoing.

We are doing the same with regard to the COVID-19 response programme, providing evidence-based advice while the programme is still underway.

Such an approach is more prevalent for humanitarian actions because of the unpredictability of many humanitarian crises, as well as their frequently multisectoral impact. But why not do the same for development initiatives?

When we aim for higher development goals and policy objectives, it often takes time for that policy to take effect. No one really knows how things will develop. There is also a multisectoral dimension to achieving the development agenda.

Evaluators must foster an organizational learning culture

Even so, we seem to cling to the old assumptions, implementing policies and programmes as if they should work as designed. We evaluate their effects five years after the fact. Why? Perhaps there are institutional issues at play, or a sense of inertia, or maybe it is easier to revert to business as usual. More than anything, then, we need to foster an organizational learning culture.

We need a learning culture in which we are not afraid to admit that things are not working out as expected and be prepared to take adaptive action. We need a regime to monitor results more regularly ‒ and not just quantitative data to show how things are going, but qualitative data to understand the underlying causes.

To make this new approach work, we need managers at all levels to embrace it: a focus on results, regular monitoring and analysis, learning and adaptation. This cannot be the responsibility of evaluators alone, but must involve the whole organization. It is a challenge that evaluation offices can help organizations to tackle, however ‒ and very much a new task on our horizon.