My contributions

This was the theme that brought together high-level representatives from Benin, Senegal, Tunisia and Morocco, who shared examples of innovations in their national monitoring and evaluation systems in an online panel organised during the gLOCAL Evaluation Week 2022. Some of the M&E innovations presented were procedural, such as the reform undertaken in Tunisia to improve the management and evaluation of troubled projects, which led to the development of the Unified Framework for the Evaluation of Public Projects and the informatization of their monitoring. Other innovations presented, however, were methodological, such as the rapid evaluations and facilitated evaluations in

In this context, during 2019-2020, the IFAD independent office of evaluation (IOE) conducted a corporate-level evaluation of IFAD’s support to innovations between 2009 and 2019 (link to the Evaluation report). This was a challenging task, not least because of the varying interpretation of what is an innovation.

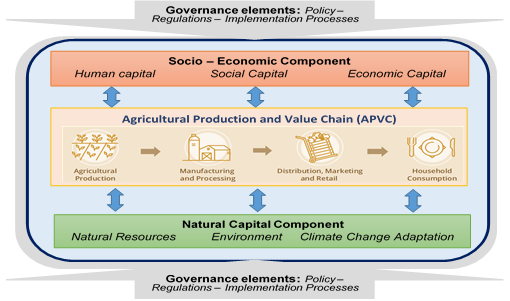

The evaluation applied mixed-methods. It analysed 508 loan projects, 240 large grants, and undertook case studies in 20 countries. A systems approach was applied leading to an analytical grid, which includes 4 components (macro domains) of the agri-food system and 12 subcomponents as presented in the Figure below.

Source: Adapted from TEEB

KOUESSI MAXIMIN ZACHARIE KODJO

Lead Evaluation Officer IFADDear Elias, Dear colleagues.

The questions asked are relevant, but the answers vary according to the context of the experiences. For my part, I have been working in the fields of monitoring and evaluation for about 20 years, with a major part (60-65%) in monitoring and the rest in evaluation.

In relation to the first question, yes, the first resource for decision-makers is monitoring data. In this respect, various state services (central and decentralised, including projects) are involved in producing these statistics or making estimates, sometimes with a lot of effort and errors in some countries. But the statistics produced must be properly analysed and interpreted to draw useful conclusions for decision-making. This is precisely where there are problems, because many managers think that statistics and data are already an end in themselves. This is not the case at all, and therefore statistics and monitoring data are only relevant and useful when they are: of good quality, collected and analysed at the right time, used to produce conclusions and lessons in relation to context and performance. This is important and necessary for the evaluation function that has to follow this.

So in relation to the second and third questions, in view of the above, a robust evaluation must start from existing monitoring information (statistics, interpretations and conclusions). One challenge that evaluation (especially external or independent) always faces is the availability of limited time to generate conclusions and lessons, unlike monitoring which is permanently on the ground. And so in this situation, the availability of monitoring data is of paramount importance. And it is precisely in relation to this last aspect that evaluations have difficulty in finding evidence to make relevant inferences about different aspects of the object being evaluated. The Evaluation should not be blamed if the monitoring data and information is non-existent or of poor quality. On the other hand, one should blame an evaluation that draws conclusions on aspects that suffer from lack of evidence, including monitoring data and information. So the evolution of evaluation should be concomitant with the evolution of monitoring.

Having said that, my experience is that when evaluation is evidence-based and triangulated, its findings and lessons are very well taken on board by policy makers, when they are properly briefed and informed, because they see it as a more comprehensive approach.

This is my contribution