Experienced Senior Manager with a demonstrated history of working in the international development industry, for a wide range of financiers (including FAO, IFAD, WB, EU, MFA Finland, Danida, etc.), NGOs and directly for governments. Skilled in International Project Management, Food Security, Sustainable Development, Capacity Development, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), Natural Resources Management and Rural Development. Specific expertise in gender, human rights based approach and evaluations.

Strong consulting professional with a Doctorate Social Sciences - under work (focused on Development Studies) from University of Helsinki. Earlier degrees in Social Sciences (Masters) and Veterinary Science

My contributions

Disability inclusion in evaluation

DiscussionNeutrality-impartiality-independence. At which stage of the evaluation is each concept important?

DiscussionIn this context, during 2019-2020, the IFAD independent office of evaluation (IOE) conducted a corporate-level evaluation of IFAD’s support to innovations between 2009 and 2019 (link to the Evaluation report). This was a challenging task, not least because of the varying interpretation of what is an innovation.

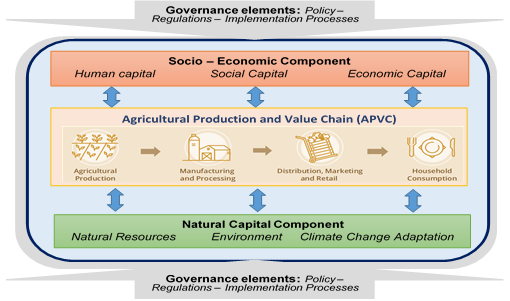

The evaluation applied mixed-methods. It analysed 508 loan projects, 240 large grants, and undertook case studies in 20 countries. A systems approach was applied leading to an analytical grid, which includes 4 components (macro domains) of the agri-food system and 12 subcomponents as presented in the Figure below.

Source: Adapted from TEEB

Pamela Dianne White

Senior Manager Cowater International Finland OyI am certainly no expert on this topic, but it is something that I have struggled with (and I look at it here as both an implementer and as an external evaluator). The difficulty I find is that inclusion of people with disabilities is only one issue among many in implementation and evaluation. For instance, bilaterals or the UN are starting to talk about disability, but we still don’t see much evidence of inclusion in practice (other than perhaps individuals receiving support in some form of income generation). Even with the interest to work more on the topic, there isn’t much inclusion to actually evaluate! It is early days as yet and there are so many topics that project teams are asked to look at, including caste, ethnicity, gender/sex, youth/age, poverty and remoteness, in addition to the actual project thematic topic itself (eg. agriculture, water supply, etc).

In our Finnish (and EU) funded projects in Nepal, it was feasible to take some actions on implementation (and staff training) as we had the hands-on team in place at local level – but I still question how big a contribution we could make. I feel like it is often easier to work on the topic as an NGO, where you are more able to give individual attention, rather than a big project working at scale.

The greatest difficulty in addressing this, in my opinion, is that disability comes in so many forms and needs different approaches, including in evaluation. Generally speaking, we can bring together groups that are differentiated by sex; or caste; or ethnicity – and ask for quotas, targeted activities, focus group discussions, etc. Of course, not everyone in that group of women, for instance, will have the same interests, but they will have the opportunity to participate. But an activity that suits a blind person may not suit someone with a mental disability. And I have often found that people with physical disabilities – especially following an injury – often don’t identify themselves as being a person with a disability (PWD). I have also heard that there is even conflict within groups sometimes – with for instance, Brahmin caste PWDs being upset about being included in a group with Dalit PWDs, though I haven’t seen this personally. I recently was involved in a GALS training process in Tanzania, and we required participation by people with disabilities as well as religious leaders, youth groups, entrepreneurs, etc. But it was clear that while the people with physical disabilities could participate well, those with mental disabilities struggled.

There are also practical barriers to inclusive evaluations. Generally, the budget for evaluations is not large and I really doubt that many development partners will be keen to pay more for projects that are not specifically disability focused. While I agree that there are steps that can be taken to be more inclusive, they are potentially a lot more expensive in terms of time and money. And as I am sure all evaluators can recognise, we often carry out flying visits during evaluations (even getting into more remote areas away from the road is difficult), and may struggle to get a representative selection of the community for focus groups, etc. It may not be possible in the time available to visit the homes of PWD, nor for them to physically reach the meeting area. Access for evaluators or staff with disabilities is also problematic in rural areas. We had some experiences in Nepal, for instance, taking a blind interpreter to the field, but it was pretty challenging, due to the difficulties with access. The young woman got terribly car sick on the winding roads, exacerbated by not being able to look forwards on the road, etc. – and needed a lot of help trekking uphill. More like a good example to us and the community, rather than something that we could replicate easily. And we had to say no, on one occasion, to a potential wheelchair bound evaluator in the mountains, as it simply isn’t feasible to get out of the car in the rough ground. Again, if you aim to represent all sectors within the evaluation team, then having women and men, and a spread of caste/ethnicity, as well as a PWD, along with the required thematic expertise and language skills, is virtually impossible. We also can’t assume that an evaluator from a specific group will necessarily be more sensitive to the issues of that group. Obviously we should, however, ensure that the evaluators in a team discuss potential disability issues and have an open mindset.

Sounds a bit defeatist, I realise. We can do some things to promote inclusion in evaluation. Use of online methods can assist us to reach people in remote areas – but this requires that they have access to a smart phone or laptop and expertise or assistance. And while this works for individual meetings – or several with their own connection – it doesn’t work for focus groups in a community setting. Invite participation of everyone in meetings, and enquire who isn’t participating, and who in the community may have a disability. Ensuring that if the disaggregation of data has extended to disability, then we report on this. If it hasn’t, then it is a recommendation for the project team. Encourage the project to provide sensitization/training on issues of disability for their staff (simple exercises like getting them to use crutches or a wheelchair are a great way for them to really feel the issues, rather than theoretically understanding them).

I am interested to hear more ideas from others for making evaluations more inclusive – beyond the obvious “ensure there is sufficient budget”.

Good luck to everyone on this challenging issue!